Donald Ranard was an English teacher in Laos from 1973 to 1975 under the Fulbright program. One of Donald’s published works is a telling of his experience during the communist takeover of Laos, which occurred not long after the communist takeover of Vietnam. Donald’s story is compelling, and well written, please enjoy it.

A Week of Living Strangely, Many Years Ago in Laos

Donald A. Ranard

(Originally published as “Yankee Goes Home” in Travelers Tales by Solas House)

Pathet Lao

“Nine years, and they give us an hour to get out,” Ruth Stone said to the Frenchman. Ruth was the wife of Sandy Stone, the head of the U.S. Agency for International Development in Savannakhet. She was standing next to an airstrip, and like the rest of us, she had two bags with her. In them, she’d packed her jewelry, some letters and photos, a few keepsakes, and enough clothing to get her through the next couple of days. Everything else—the Thai teak furniture, the Lao silver repoussé bowls, the Chinese blue and white porcelain, the Vietnamese pearl-inlaid lacquerware, and all the bric-a-brac accumulated from thirty years of living overseas—Ruth had left behind in the big French colonial house that had been her home for the past nine years.

The Frenchman, an old Indochina hand who ran the French cultural center, had come to say goodbye. It was May 22, 1975. Three weeks before, Americans had fled Saigon, one step ahead of the communists. Now we were being kicked out of Laos.

A C-47 appeared in the sky—6:30, right on time. A few minutes later, as a tall American wearing aviator sunglasses and cowboy boots ambled across the tarmac, it occurred to me that this may have been the first time in my two years in Laos that things had gone according to plan.

“Bon chance,” the Frenchman said, shaking our hands. He seemed sincere in his sympathy, but I wondered how he really felt. Not so many years before, the Americans had watched the French give up their empire in Indochina. We had arrived on the scene confident we would succeed where the French had failed. Now we were leaving, and the French were staying. It had been a week of living if not dangerously, exactly, then strangely.

A small, dusty town on the banks of the Mekong River, halfway down the Laotian panhandle, Savannakhet was the quintessential tropical outpost, an out-of-the-way place in an out-of-the-way country. Upriver was Vientiane, the capital, with its wide, shady boulevards, crumbling colonial buildings, and floating world of foreigners—backpackers and expats, stringers and spooks, foreign aid workers and drug runners. In north central Laos was the royal capital of Luang Prabang, where the king lived, the country’s most traditionally Lao city, and one of the loveliest places in Asia, a riverside town of golden temples, surrounded by mountains. Every now and then a particularly adventurous traveler would wander into the wilder regions of the country, where Burmese, Thai, and Chinese warlords vied for control of the opium trade, or sneak into the secret city of Long Cheng, the nerve center of the CIA’s covert war in Laos and the country’s second largest city, although it appeared on no maps. The city sat on a high plain surrounded by strange, humpbacked mountains shrouded in mist, an opium smoker’s dreamscape. With its state-of-the-art telecommunications equipment, endless air traffic, dirt-floor village huts, and barefoot Hmong soldiers—some as young as ten—carrying M-16s, Long Cheng brought to mind a writer’s comment, “The only thing modern about Laos seemed to be the war.”

But no one came to Savannakhet. The small town proper was a mix of crumbling French colonial architecture, Chinese shophouses, and one and two-story cement block buildings. In my two years as a Fulbright English teacher in the local French-medium lycée, I could remember only one tourist, a beautiful French girl, a hippie with a serene smile and an opium habit, who had somehow wandered off the world traveler trail and down to Savannakhet.

Then two weeks after the fall of Saigon, in a turn of events no one would have predicted, sleepy Savannakhet suddenly found itself in the media spotlight, the object of world attention.

All that year, there had been antigovernment demonstrations, led by students and orchestrated by the North Vietnamese-backed Pathet Lao, against the U.S.-supported Royal Lao government. The war by then was officially over; the two sides had formed a coalition government, the third such attempt at national reconciliation in fifteen years. The U.S. had sabotaged the first, in 1958, and both the U.S. and the North Vietnamese had undermined the second a few years later. Not for nothing would the Lao complain that they could work out their differences if outsiders would just leave them alone: In a tiny country where everyone in power seemed related, where one of the Pathet Lao leaders was a half- brother of the prime minister on the other side (and both were members of the royal family), the improbable was first cousin to the possible. But whatever chances for success the first two coalitions might have had, few held out hope that the third would work. The Pathet Lao already controlled most of the countryside. Now, urged on by the North Vietnamese, they moved to take over the towns as well: Why share power when they could have it all?

Elsewhere the communists might have turned to the intelligentsia to rally the workers, but in a country with almost no college education, where only a small percentage of children attended secondary school and many didn’t go to school at all, there was no real intelligentsia to rally the workers, or workers to be rallied, for that matter: Laos barely had any industry. And so, in the absence of anyone else to turn to, the Pathet Lao had turned to the closest thing the country had to an intelligentsia, 16- and 17-year-old high school students—my students—to whip up support for them in the towns.

It wasn’t that hard a job. After two decades of war and grossly corrupt government, people were ready for a change, any change. Laos had the distinction of being, per capita, the most heavily bombed and lavishly aided country in history. The U.S. had rained down bombs on its enemy and aid on its allies. The bombs—two million tons of them, two thirds of a ton for every man, woman, and child in the country—had turned vast areas of northern Laos into a moonscape of ruin, but had, arguably, done less damage to enemy morale than aid had done to the U.S. cause. We paid for almost everything, including the entire cost of the army, the police, and the diplomatic corps, so that suddenly one of the least economically developed countries in Asia—a country that still had one traffic light in its capital after five years of U.S. aid—was awash in American money. Generals salted away millions, while the rural poor remained poor and the urban lower middle class lost ground: Another consequence of aid was inflation. In Vientiane, corruption even had its own monument, an Arc de Triomphe knockoff called the “vertical runway” because—so the story went—it had been built with USAID concrete intended to improve the airport.

Eventually, unable to control the corruption, the U.S. had simply moved in and taken over. The embassy made the important political decisions, the U.S. Air Force and CIA ran the war, and USAID took care of most everything else, creating in effect a parallel government, with its own departments of agriculture, education, rural development, health, and public administration. In Vietnam, Americans served as advisers to the Vietnamese government. In Laos, it was the other way around: The Lao served as advisers to us—and made higher salaries than the senior Lao civil service. American aid, a French report said, was “a substitute for national effort.” In fact, at the peak of U.S. involvement, Laos was perilously close to an American colony.

To be sure, American aid had done some good. It had built hospitals and schools. It was responsible for that rarest of things in Laos, a good idea that actually worked—the Lao-medium Fa Ngum secondary school system, created for the less privileged as an alternative to the French lycées that had been serving the children of the elite since the colonial era. And if the typical USAID official seemed to be a paunchy, desk-bound retired military man with an unusually astute grasp of the perquisites of his position, there were other Americans, generally younger, usually lower level, who cared deeply about the country, who had thought about the pitfalls and unintended consequences of aid, the perils of its imperialistic hubris, and who believed that they should be helping the Lao build a better version of Laos, not a Lao version of America. But whatever good the agency had done, if the point of aid was to help the poor and build local capacities, it was hard to escape the conclusion that when it came to international development, Laos had been a near-perfect case study in how not to do it.

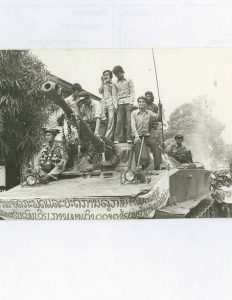

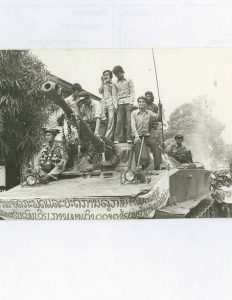

Photo: Ray Oram

There had been an anti-American edge to the demonstrations, but after the communist takeover of Saigon, the U.S. became the main target. For years, Savannakhet had been considered a bastion of the right, but on the afternoon of May 14, a group of secondary school students proved their revolutionary mettle when they stormed the small USAID compound and took the three Americans they found there hostage. The students marched the Americans down to the newly liberated governor’s residence, and crossing the palm tree-shaded lawn, they entered the big, whitewashed French colonial mansion where the Americans had once attended parties and where they were now put on trial for crimes against Laos.

Fortunately, Sandy Stone, the head of the USAID mission in Savannakhet, had been at the office that day, and Clem, one of his assistants, had not. There was no telling how Clem, a tightly wound ex-Marine from hardscrabble Pennsylvania, might have reacted; a few days later, when he heard that the Pathet Lao were on their way to Savannakhet, he would threaten to dig up an M-16 he’d buried in his yard and take on the commies himself. Stone, a retired Army major, was Clem’s temperamental opposite. He didn’t speak Lao, or know much about the culture, but he had the right personality for the place. Stone had the two qualities that mattered most in Laos, equanimity and a sense of humor, and it didn’t hurt that he was short for an American, not much taller than the Lao.

At the time, there was an embassy booklet on evacuation procedures being circulated among Americans in Laos. “Bend with the Wind,” it was called, and Stone knew how to bend. He waved to the standing-room only crowd, as he entered the governor’s mansion, and several in the crowd waved back. He exchanged quips with a few of the students he recognized, then listened patiently to the harangues about CIA and corruption. He calmly denied the CIA charges, and didn’t get upset when students jeered as he tried to talk about the good work USAID had done—the refugee assistance, the fish ponds, the roads, the schools. By then it was dinnertime, and everyone was hungry. Four hours after they had stormed the USAID compound, the students let the Americans go.

Even the most anti-American students had been impressed by Stone’s performance. But no one believed his denials about the CIA, a few students told me later that evening, when they dropped by our house to recount the episode. And they were sure that the old man with white hair, Mr. Charles, was CIA too. The only one they weren’t sure about was the young guy; of the three, they liked him the most, because he seemed genuinely sympathetic to the students and their cause. But as they described him—tall, with stylishly long hair and a mustache—I realized they were describing the one man I knew for a fact was CIA.

I admired Stone for his cool and skillful restraint, but behind his unflappable composure was a strangely upbeat mood at complete odds with events. When I heard that he was telling everyone not to worry, we weren’t leaving—this thing would blow over—I realized he was in the grip of a delusion. It was the same delusion that a few weeks before had caused Graham Martin, the last American ambassador to Saigon, to ignore all signs of collapse and to insist that the South Vietnamese capital would not fall and that the U.S. would not desert its ally. Like Martin, and most of the senior Americans in Vietnam, Laos, and Washington, Stone had had his formative professional experience in World War II, serving in the European theatre as an officer in the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA. He had participated in one of the great achievements of the twentieth century. The notion that the U.S.—a country that had beaten the two greatest military powers in the world, Germany and Japan, then rebuilt their societies from the ground up, helping to turn them into world class economies—was going to meet its match in Laos was inconceivable to him, and now that it was happening, he was unable to absorb the information.

The Americans had been released with the promise that they would stay in their houses. It was house arrest Lao style, which is to say it was loose, unclear, and always negotiable. My situation, as an American teacher, was even more ambiguous. To a handful of my students, the ones I’d been closest to, the fact that I was their teacher overrode everything else, and they continued to drop by and update me on the situation. But to most of the students, I’d become a liability, someone who could get them into trouble, and they stayed away. A few, including one or two I’d been friendly with, decided I was the enemy; the fact that I spoke Lao only made me more suspect.

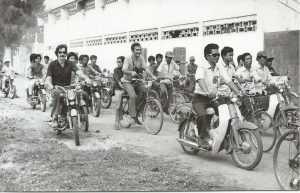

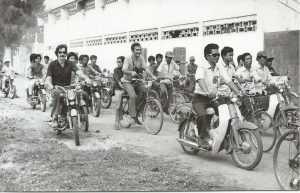

Photo: Ray Oram

I was less afraid of any attack directed at me personally than I was of a general breakdown in law and order. Ever since the fall of Saigon, high-ranking government officials had been fleeing across the river to Thailand, and it wasn’t clear who, if anyone, was in charge. Everybody seemed to be carrying a weapon; some of my students had made their own zip guns. One evening, across the street from the outdoor restaurant where we were having dinner, we watched a man with an AK-47 rob a jewelry store and then shoot and kill the Chinese shop owner as he sped off in his getaway samlor, the motorcycle with side car that served as a taxi. The next day, as I was riding my Honda on the outskirts of town, I passed a boy carrying an old rifle. We exchanged greetings, but something about his smile persuaded me to gun the bike and lie flat on the gas tank.

Ever since then, I’d been staying close to home, a crumbling French villa on the Mekong River that I shared with Mike, a British volunteer who taught English at the lycée with me. But on the afternoon of May 21, when one of our students came bursting through the screen door and into our living room, yelling, “Pathet Lao, maa-lay-o“—the Pathet Lao have come—it took me no time to make up my mind: How many chances in life do you get to witness a revolution?

I hopped on my Honda and headed out of the compound, onto the main road—and into the first traffic jam in Savannakhet’s history. Usually empty except for a bicycle or two, the road was choked with motorcycles, scooters, bicycles, and samlors. The mood was festive; we might have been on our way to a boun, the traditional Lao celebration that always seemed to be going on at one temple or another.

In town, people had lined up on both sides of the street to watch Chinese boys perform a dragon dance. Vendors sold grilled pieces of chicken and squid and plastic bags of lemonade. Western reporters and camera men perched on the tops of two-story buildings; one reporter, a middle-aged man in a bush jacket, looked vaguely familiar from U.S. network news.

The crowd let out a cheer as the convoy came into view. The Pathet Lao commander sat in the head vehicle, an old jeep with a back flat tire, giving the people their first look at life under communism: ka-plunk, ka-plunk, ka-plunk. After the jeep, came canvas-covered trucks full of soldiers in green khaki and floppy Mao-style hats. They were young—younger than my students, many of them—and dark skinned, and behind the impassive expressions I sensed the wariness of villagers on their first trip to town. Students jumped up on the trucks and joined the soldiers, posing for friends who ran alongside taking pictures, and when I saw them, the smiling, fair-skinned sons of the elite, in their bell-bottom pants and Lacoste polo shirts, next to the grim soldiers in their baggy, threadbare uniforms, I felt fear for my students. This was not a friendship that was going to last.

An old Soviet tank coughed, sputtered, and rattled into view. The tank commander, a small, dour man, straddled the gun barrel, his arm raised in stiff salute, Third Reich style. The effect was unintentionally comic—Charlie Chaplin playing the Führer—and children ran alongside the tank, their arms raised in mock salutes. In the center of town, the convoy stopped, and a small contingent of women in gold-embroidered silk dresses placed garlands of flowers around the soldiers’ necks, then tied white strings around their wrists in a Lao ceremony of welcome.

“Strange place, Laos,” said an Australian journalist, standing in the crowd next to me. I knew when I first saw him that he was new to Laos; he had that look of bafflement on his face that newcomers always wore, the same expression that I had worn for most of my first year. He had flown in from Vietnam with his story already half-written, expecting to see the same panic and bedlam he’d seen in Saigon. His first clue that things in Laos were going to be different occurred a few minutes after he arrived, on his way into Vientiane from Wattay airport, when he saw a group of men and women up ahead marching alongside the road. Oh, good, he thought, a demonstration, and he told the taxi driver to slow down. But as he drew closer, he saw that they weren’t demonstrating, they were. . . dancing, and the women were actually men dressed up as women, and some of the men, stripped down to their waists, their faces and bodies blackened, were sporting huge plastic phalluses “Boun Bang Phai,” said another passenger, a Frenchman. “It’s a fertility festival.”

The journalist leaned out the window to take a picture, and one of the dancers whipped out his own camera, pressed a button, and a tiny phallus popped out of the lens. The bloody country’s on the verge of collapse, and men are running around in women’s clothing, the journalist thought in amazement.

At 5:30 the next evening, we got word from Stone: Be at the airport at 6:30. We were already packed and ready to go, having anticipated this moment for a week. What we couldn’t fit into our bags we gave away to two students who came to say goodbye.

I took one last look at the house that had been a gathering place for students, who had come to borrow books, listen to music, and practice their English. I’d learned the language and studied the culture and assumed I was different from the Americans who never made the effort. “Welcome aboard,” Sandy Stone had said when I arrived; at official functions, he would introduce me to people as “our Fulbrighter.” I didn’t like the sound of that, and kept my distance from the other Americans. We all had our illusions in Laos; mine was that I wasn’t part of the great, strange, doomed American enterprise there.

I walked out to the road with Mike and Ray, another British volunteer, and flagged a samlor. As we started to climb in, one of my students rode by on a bicycle. He smiled and waved at me, as if it was just another day, and he had all the time in the world.

“Bloody hell,” said Ray, laughing. “Hasn’t he heard there’s a revolution going on?”

The student stopped.

“Pai sai?” he said. Where are you going?

“Yankee goes home,” Ray said.

***

Donald A. Ranard is an award-winning writer whose work appears in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, New World Writing, The Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, The Best Travel Writing, and many other publications. His play, Elbow. Apple. Carpet. Saddle. Bubble., about a wounded Afghanistan War veteran, placed second in Veteran Repertory’s 2021 playwriting contest. Based in Arlington, VA, he has lived in 10 countries in Asia, Europe, and Latin America.

Joe’s blogs are copyright protected ©, you are welcome to share them on Facebook and other media, in their entirety, crediting Joe and his guest writers, when applicable, for the articles.

Updated: September 7, 2022 at 11:32 pm

About the Author

Joe Campolo Jr.

Joe Campolo, Jr. is an award winning author, poet and public speaker. A Vietnam War Veteran, Joe writes and speaks about the war and many other topics. See the "Author Page" of this website for more information on Joe.

Guest writers on Joe's blogs will have a short bio with each article. Select blogs by category and enjoy the many other articles available here.

Joe's popular books are available thru Amazon, this website, and many other on-line book stores.

Excellent details, beautifully nostalgic and realistic portrayal of a time that needs to be documented and remembered. Superb story telling.

Thank you, Laurie–much appreciated.

Good story. During the Vietnam War years LAO’s had very few physicians, insufficient body storage for a morgue and pathology services were non existent. The only people available to triage anyone were a few physicians and former special forces medical sergeants working as public health workers, researchers, and medics. For a really good picture of pre and post war Laotian life one should read the stories of Colin Cotterill about his character, Dr. Siri Paiboun, a 72-year-old medical doctor, has been unwillingly appointed the national coroner of newly-socialist Laos. His lab is underfunded, his boss is incompetent, and his support staff is quirky to say the least, Cotterill’s sense of humor and his unbelievably detailed knowledge of the customs, culture, professions, and lifestyles of Laotians will paint the picture in technicolor for you.

Thanks for the information Art, very interesting.

Thank you. I read Cotterill’s first book, The Coroner’s Lunch. Not many writers are able to write so convincingly from the point of view of someone from an entirely different culture.

Having served with Don in Savanh and having been one of the evacuees on the same C-47, I can attest to the accuracy of his account. His colorful portraits of the Americans and Lao students are — as they say — “impactful” and memorable. He also wins the award for the best Marlon Brando look alike on a motorbike in a crisis. I look forward to more of his work.

Chris, I remember at one point–I think we were on the C-47 or about to board it–you turned to me and said, “Do you realize we’re living history?” And I thought, you’re right, and I made a promise to myself to record it as well as I could.

Brando, eh? LOL, as the younguns say. Brando rode a Triumph, 650 cc, as I recall. I had a sissy bike, a 90 cc Honda. He was the Wild One. I was the Mild One.

Don – mild in manners, more wild in thought, perhaps? This is a great account of what was indeed a historic day. I remember the look on the face of Sandy’s wife, aghast at the thought that all their memorabilia, which decorated their house and which had been collected over a career’s worth of foreign service in different countries, was to be left behind, “perhaps” to catch up with them after evacuation. I doubt that ever happened.