Introduction

Cambodia, a nation upended by colonialism, war and genocide in the twentieth century, is still a very poor nation. Jerry Collins, who taught writing and Asian studies on American military bases in Asia for over 20 years for the University of Maryland/Asian Division, shares his experiences from two trips to Cambodia in the early 1990’s. Jerry’s experiences provide interesting insights into that time.

***

You Can Get in Now: When Cambodia Was at War

Jerry Collins

I couldn’t tell if he meant me any harm. He was holding an AK 47, and I didn’t understand what he was saying, but in the darkness I could see his eyes, and they didn’t seem malicious. I was standing next to my rented motorbike that had run out of gas, waiting for my friend Dave to return. We had been coming from Angkor Wat and had left later than we should have. Now it was dark, and Dave had gone ahead to get gas at a roadside stand where they sold it in old plastic soda bottles. As I waited on the narrow road, two motorbikes with four guys on them pulled up suddenly. They all had rifles. The one closest to me started talking to me in Khmer. Terrified and knowing they wouldn’t understand anything I said, I stared at his eyes — pretty much the only thing I could see at first — and pointed to the gas tank and tried to mimic that I had run out of gas. He seemed amused. They all did. They all looked like they were 14, which meant they were probably 18. I was beginning to think I was going to get through this. They seemed to have stopped because they were curious. As I tried to tell them everything was OK, Dave arrived with a 7up bottle filled with the magic liquid —- my ticket out of there. The young guys laughed and left, and I put the gas in the tank.

As I was getting back on the bike, I said to Dave,

“Maybe coming here wasn’t such a great idea.”

He replied,

“Well, we did know that there was a war going on. Welcome to Cambodia.”

When I set out on my Christmas vacation in 1993 from my teaching job in Japan, I hadn’t intended to go to Cambodia. I had arrived in Bangkok intending to travel on to Vietnam, which had recently opened up to tourists. On the night I arrived, I went to visit a couple of American friends by taking the water taxi (a long boat) on the Chao Praya River. As I was standing on the dock, I saw a young hippy-looking guy sitting on a bench behind me wearing a T-shirt with a picture of Angkor Wat. I asked him where he got it, and he said Angkor Wat.

“You got into Cambodia? How did you that?”

“You can get in now,” he said.

I was shocked that getting into Cambodia was possible. The Vietnam War had ended twenty years before, and it had taken that long for Vietnam to open up to travelers. But Cambodia remained in a state of war, its latest a civil war between the communist Khmer Rouge (Red Khmers) and the feeble and fledgling government. I was particularly interested in Cambodia, fascinated by all I had read of its history and culture. It was exotic and a land of contrasts, but lots of places are. Almost every travel article I’ve ever read talks about the place being “a land of contrast.” (Which is why I don’t read many travel articles.) Exotic and “land of contrasts” are cliches. But mysterious, tragic and foreboding are not. I had hoped for a long time that its war would end, and it would be possible to travel there when it was at peace. It simply never occurred to me that I could travel there while a war was going on.

A Brief History

Cambodia, along with the other countries of Indochina (Indochine) — Vietnam and Laos —- gained their independence from France in the mid 1950’s. Cambodians today think of the period from 1953 to 1970 as the “good years,” the years the country, under its King, Sihanouk, prospered. It was a time of peace. But in the late sixties, when Sihanouk allowed the North Vietnamese communists to move troops into Southern Vietnam through eastern Cambodia as part of its war against America, he not only alienated the Americans, but also exacerbated tensions between the Vietnamese and the Khmer people that had existed for centuries. The Khmer Rouge formed and supported the Vietnamese communists, and an anti Sihanouk faction formed within his own government which deposed him. A republic — of generals — replaced the monarchy.

In order to stop Vietnamese operations in Cambodia, the Nixon Administration began to secretly carpet bomb the Eastern part of the country bordering on Vietnam. On Friday, May 1, 1970, Nixon invaded Cambodia and college campuses in America exploded in protest. On May 4th, four college students were shot to death by National Guard troops on the campus at Kent State in Ohio.

Five years later, on April 17th, 1975, the same month that Vietnam and Laos fell to the communists, the Khmer Rouge marched into Phnom Penh. What followed was one of the most brutal and horrific chapters in world history. Led by Pol Pot, who was to distinguish himself as one of the most thorough mass murderers in history, the Khmer Rouge declared 1975 to be Year Zero, the beginning of a new world. The past was erased. Enemies of the state — intellectuals, students, urban people, middle class people —- were sent to the countryside to work, or they were tortured and executed. Intellectuals were often defined simply as people who wore glasses. Over the next four years, close to two million Cambodians died in a country with a population of eight million. It was unlike any other form of genocide the world had ever seen; it was auto genocide — genocide committed against one’s own people and not connected to race, religion or nationality.

The carnage ended only when Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1979 and became bogged down in an occupation that lasted until 1989. A treaty in 1991 officially ended the occupation, but it didn’t bring peace. The United Nations oversaw an election which instituted a new government in September, 1993. But the countryside was still controlled in large part by the Khmer Rouge, and it went to war against the new government. And even though it was still going on, this kid was telling me I could go. I was stunned.

The Journey

The next day, I purchased a ticket to Phnom Penh, not Saigon, and at 5 am the following morning I boarded the shuttle bus from Khao San Road to the airport. Just after I sprawled across the back seats of the bus hoping to get a little sleep, I heard someone enter and bellow “Howdy,” to the people sitting in front of me. Oh, no, I thought, a loud American. I pretended to be asleep. It wasn’t until I got off the shuttle that I started talking to Dave, a 47-year old engineer who lived in Mendocino, California. We flew to Phnom Penh together and took a taxi into town after we arrived. The driver showed us a number of guest houses, and we settled on one built in a colonial French style. Each of us rented a spacious, but plain, room for $10, and after we dropped off our stuff and came back out to the front lobby, we found the family who owned the place sitting on blankets on the floor about to start lunch. They insisted that we join them. We spent most of the next hour sitting Buddha style on the floor as part of the family circle, eating rice and vegetables, soup and grilled fish and tasty pastries. Welcome to Cambodia!

We walked around the city which had once been called the “Paris in the East,” one of the most beautiful cities in Asia in the 19th century. It was now in a very visual way a shell of its old self. Old shop signs in French — pharmacie, boutique —- remained, but the shops were either closed or understocked. Dilapidated cinemas featured large Charlie Chaplin posters, but no movies were playing. (Chaplin had been very popular in France, and so he was in French Indochina as well.) The wide boulevards the French built were lined with rubbish and piles of dirt rather than cafes which once sold coffee, crepes and croissants.

Two places tourists could visit were the killing fields, a place where the skeletons of the victims were piled and displayed, and Tuol Sleng Prison, where much of the torture had taken place. “The Killing Fields” became the name of a movie which won eight academy awards, and which, I’ve read, was largely inaccurate. I’ve never seen it. And I couldn’t find the courage to visit the place. I did visit Tuol Sleng, now called the Genocide Museum. That was enough.

The city is situated just north of the confluence of the Ton Le Sap and Mekong Rivers. The Ton Le Sap, the only river in the world that naturally changes direction twice a year, is fed by a lake of the same name which pushes the water 93 miles southeast to the Mekong River in the dry season from November to April. When the rains come, the river flows back and feeds the lake and its distributaries. The swollen distributaries were used to transport the stone used to build the temples of Angkor and for millennia have provided fresh fish to the population. This process created the wealth which enabled the area around Angkor to be one of the most powerful kingdoms in Southeast Asia from the ninth to the fifteenth centuries.

Now the promenade along the river was an eyesore of broken concrete and unkempt bushes. Across the street, poorly attended Buddhist shrines in a devoutly Buddhist country spoke to the poverty of a city reduced to rubble and destitute homeless people, some of them, particularly at night, begging for money. Yet, what struck me the most was the cheeriness of the people. Friendly, smiling, easy to laugh. It made me realize why French colonizers, and colonizers in other Asian countries, often thought of and referred to local people as children. Aside from being generally smaller than Europeans, their happy-go-lucky demeanor would be easy to misread as childish. But, of course, there was also the brutality. Not long before we arrived, 33 Vietnamese living in a village on the eastern border had been massacred by local Khmer people. I forget now what the provocation was, but it hardly matters. It resulted in a massacre. A country of contrasts, indeed.

At night we took in the scene at the newly opened Foreign Correspondence Club that overlooked the Ton Le Sap. Journalists sat in the back of the large restaurant on the third floor taping away on typewriters while backpackers and UN workers and local Khmer elites mingled and drank and ate delicious two dollar meals. Best black pepper I’ve ever tasted. Especially with fresh garlic on fried shrimp.

I made friends with Joan, a middle-aged Australian woman who managed the place and whose dour-faced husband worked on some Aussie -run developmental project outside the city. She introduced Dave and me to an American, Bill, who had lost a leg in the Vietnam War. Incredibly, he was from Mendocino, and his son used to hang out in Dave’s house with his two sons. He was there as part of a $2-million project provided by the Agency for International Development. He managed a factory that hired local people, some of them disabled, to make prosthetic devices. (Cambodia is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world.) He took Joan and me to the factory one day to see how it operated.He wasn’t a particularly friendly guy, but he knew interesting people — activists who hated the Khmer Rouge but didn’t like the government either. Some were American vets, and some were local people. He took Dave and me to a large house to meet them one night and to get their spin on the political situation. We drank tea and listened. When we asked a question, we were given detailed answers by one of them standing in front of a large map using a pointer. They were passionate, but their prognosis was grim.

One night at the bar of the FCC I spoke to Nate Thayer, a freelance journalist and contributor to the Far East Economic Review whose analysis was highly respected and valued by people interested in the Cambodian situation. For much of the time that he pontificated and gesticulated I wondered what he was stoned on, but I couldn’t deny his impressive knowledge and understanding of Khmer culture. He claimed he was going to interview a couple of Khmer Rouge generals in a couple of hours. I was skeptical, but when he told me that they routinely stayed in hotels in Phnom Penh, and that they were heavily involved in smuggling operations, I believed him. It was undeniable — corruption was rampant in the country, and it was no surprise that money trumped ideology. They conspired with corrupt Thai officials on the Cambodian/Thai border to cut down trees illegally, which were transported to Trat, a small coastal town in the Gulf of Thailand, where they were shipped to the Philippines to be converted into products sold on the world market.

On another night, Joan suggested that we drive around the city after the restaurant closed. After everyone left and we were about to leave, a young Khmer guy came up the stairs and walked over to where we were sitting; she nodded to him, and then walked to the back of the room and unlocked a large cabinet. She withdrew an AK 47 and handed it to him. He went downstairs to sit on the second-floor landing to take up his duties as night watchman.

We drove through the ruble and the ruins for a couple of hours in her sports car, stopping at a few after-hours places and ending up at the base of Independence Monument which had been built in 1953, after the French finally left. It was almost dawn, so for once it wasn’t hot. As the sun came up, a slight breeze worked its way through the monument’s stone structure. She smoked cigarettes, and we talked about how we didn’t feel like strangers in a strange land. We both felt like we belonged there, somehow.

Dave and I learned that we could either fly to Angkor Wat or take a slow boat up the river, a journey that lasted 14 hours and had been attacked “once or twice” by bandits who took everyone’s money. We decided to fly. Angkor Wat is an actual temple built between 1112 and 1152. But the term is usually used to refer to a number of temples contained within a 12-square mile radius. The Lonely Planet Guide calls Angkor Wat The greatest architectural achievement ever conceived by the human mind.

We drove around the complex for days. I made sure I didn’t run out of gas again. After a few days we returned to Phnom Penh, and after a day or two there, we took an eight-hour bus trip to Saigon. It should have only been five hours, but we had to wait for hours at the border while Vietnamese soldiers negotiated with the driver how much they could squeeze out of him. I felt ambivalent about leaving. Going to Vietnam was important, but there was more I wanted to see. I wished I had time to go Kompong Son, a coastal town which had been important during the Vietnam War. It was the place where the communists smuggled in guns. I decided it had to wait.

Back To The World

When I was back in Japan, I planned to return during my summer break, but some family matters back in America required that I return there. So, with regret, I decided to put off going back to Cambodia until the following December. If I had gone back in the summer, I would have flown to Bangkok on July 22 and gone to G&D Travel on the 23d to buy a ticket to Phnom Penh for the 24th. I would have hung out in the city for a day, happy to be back, and then I would have taken the train the next day, the 26th, to Kampong Som. But I didn’t, I went to New York instead. And that’s where I was when I read that that train on the 26th had been attacked by the Khmer Rouge. Dozens of Vietnamese and three westerners — a Englishman, an Australian, and a Frenchmen — had been taken off the train. The local Khmer people were robbed, but unharmed.

News was spotty. I went back to Asia to teach after my summer break. In October, I got the news that the bodies of the three westerners had been found. I was in the faculty lounge when a colleague told me. It was the end of the day, and it was getting dark outside. Fortunately, no one was around. I was able to be alone for a while to process the news.

And Back Again

I stayed in touch with Dave through a newfangled invention called email. He was planning to go to Laos, which had opened to tourists a couple of years before, and our Christmas vacations were going to overlap for a few days. So, I flew to Phnom Penh in order to make arrangements to get into Laos. The first place I went when I arrived was the American Embassy. I had learned over the previous year that Americans overseas can check in with the local US embassy and give details of how long they planned to be in the country and where they were staying so that their next of kin could be informed if they went missing — or if they died. It seemed like the smart thing to do.

I was astounded by how much Phnom Penh had changed in one year. The streets were cleaned up, as well as the Buddhist shrines. The development money that Western countries had poured into Cambodia seemed to be making a difference. The atmosphere was more relaxed. Things didn’t seem so grim, and the war seemed more distant. It was good to see.I knew when Dave would be in Luang Prabang, Laos, but it was difficult to get through by email from Phnom Penh. I didn’t have a laptop back then, and the internet connections at guest houses were undependable, so I couldn’t find out where he was staying. But I knew it was a small town and there wouldn’t be many places where tourists could stay, so I went, and as I walked down the street on my second day there, I heard that voice I had heard in the back of the van the year before. It was Dave yelling at his brother John as they exited a taxi outside of a guest house they were checking into.

After spending some time with them, Dave returned to America, and I went back to Cambodia with John. John was a Vietnam vet who never really fit in back in America after the war. He had spent the previous 20 years travelling the world, supporting himself by teaching English. His latest gig was teaching in Phnom Penh. He and I went back there, and from there up to Angkor Wat. When we checked in at a guesthouse, we told the owner that we wanted to see Banteay Srei, a temple complex that was built two hundred years before Angkor Wat. He told us that there were bandits on that road. The “bandits” were actually poorly paid, poorly trained and poorly treated government soldiers who began disguising themselves as Khmer Rouge and bushwacking tourists. John, the most well-travelled person I’ve ever met, said he had been there before, so it wasn’t that important to him. I decided that it wasn’t that important to me either. I wanted to go, but I didn’t.

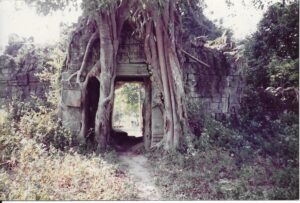

On the day before he and I were to fly back to Phnom Penh, we drove to Ta Prohm, a beautiful temple which changes in appearance, we were told, as the sun moves across the sky. But I got bored watching it change, so I drove back into town to check with the travel agent about our airline tickets back to Phnom Penh the next day. I went to the guesthouse first and found when I arrived that the owner was visibly upset. I tried to understand the problem, but I don’t speak any Khmer. She moved her right hand across her throat and said “Americans.” Then she raised two fingers. Her son, Daw, was close by, and he knew some English. He told me that a van with tourists had been robbed on the road to Banteay Srei. Two Americans who had been in the van had been shot. I told him I wanted to go to the hospital. As far as I knew, there were only four Americans in this town, and two of them had been attacked. I wanted to know what was going on. He indicated that it would be difficult for me to find, so he would take me on his motorbike.

When we arrived, I followed him through the iron gate of a compound surrounded by an eight-foot white wall. Inside were a number of single-storied French colonial houses that were probably built in the 20’s. There didn’t seem to be anything resembling a hospital. He exchanged words with local people we passed, and I followed him to a very small stone structure — one room that looked as if it were used as a storage area. In the middle of the room on top of a stone slab about five feet high, something was wrapped in immaculately clean white linen. It took a moment for me to realize that it was a corpse. Somebody told me that it was the driver of the van. Apparently, the bandits had fired a mortar shell in front of the van. Then they robbed the tourists and sprayed it with gunfire. The driver and the two Americans were all hit. I could see that Daw was shaken. I said the word “driver” to him in English, and in English he said “my friend” and started to cry.

We walked across the compound to where medical personnel were removing a man on a stretcher from what seemed to be the central building. He was a Westerner who looked to be about 60. He was attached to an IV and the blankets on top of him were covered in blood. I stood close by as they lifted him up into the back of the ambulance — and dropped the stretcher. He actually seemed to smile. They tried again and succeeded. When the ambulance left, I spoke with a French medical assistant who confirmed that the man was American and that his wife had died. I met him again on plane back to Phnom Penh the next day. He told me that the woman’s corpse was on the plane, and that her husband had been put on a special plane the night before to Bangkok where he would change planes for Singapore. Months later, I read that he survived.

Pol Pot, The End

In 1997, Pol Pot, sick and close to death, was overthrown by his Khmer Rouge proteges. His captors allowed Nate Thayer to interview him in a jungle camp where he was about to be put on trial. It was the last interview Pol Pot gave. Thayer was also allowed to film the trial. Soon afterwards the mass murderer was dead. By 1999 most of the leadership of the Khmer Rouge had been captured, and the Khmer Rouge ceased to exist.

Over the years, I have visited Dave at his place in Mendocino a couple of times and we’ve gotten together a couple of times in Thailand. And I’ve been back to Phnom Penh a number of times since the war ended. The first time, in 2001, was the most memorable. When I arrived at the landing on the second floor of the FCC, a teenage girl in jeans and sneakers, not a guy in scruffy clothes holding an AK47, greeted people on the way upstairs to the restaurant. Seeing her smiling face brought a tear to my eye. So much had changed, and so much of it for the better. Upstairs, the restaurant crowd was different. More upper-class Khmer and Westerners than before. Less frenetic. Joan was gone. The food was more expensive, and not as good. In fact, it wasn’t very good at all. But I didn’t mind. I was back in Cambodia. And Cambodia was at peace.

###

You may share this article in its entirety, crediting Joe and his guest author for the work. Copyright protected, all rights reserved © Joe Campolo Jr