If you expected everything to make sense, you were soon disappointed.

~Joe

Scrounging for Parts in a Two Hundred Billion Dollar War

For almost one month during my fun filled, all-expense paid visit to Vietnam in 1970, I was a member of an aircrew.

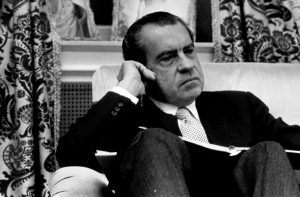

President Richard Nixon’s program of Vietnamization was in full swing, and things were rapidly changing. The program was an attempt to extricate the U.S. by turning the war over to the South Vietnamese military, in full. And the very first day the program was signed, military supplies and equipment for the unpopular war began to dry up. Of course, the South Vietnamese were nowhere near being prepared for the handoff, so the American forces at hand had to continue all of their missions, albeit with fewer supplies and equipment.

Assigned to various functions in supply, I spent most of my time at or near the Phu Cat airbase in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Scrambling for supplies and equipment was a way of life, but soon after Nixon’s program unfolded, we came in dire need of many additional items just to keep the birds flying…and the Vietcong at bay. One of the first airbases to shutdown was Nha Trang, a few hundred miles south of Phu Cat. In addition to being an airbase, Nha Trang was home to a large Special Forces operation. Around September of 1970, I was sent to Nha Trang to scrounge any materials which they may have had, that we were in need of at Phu Cat.

I was looking forward to the detail, I thought it would be a piece of cake. But as with most things in the war, it turned out to be anything but that. Nha Trang, an in-country R & R center, was right on the coast of Vietnam and was famous for it’s beautiful white sand beaches. Armed with only a pile of paper work, I hopped on a C-130 Hercules and landed at Nha Trang several hours later, eager to carry out my mission.

The Best Laid Plans of Men & Mice

Upon my arrival at Nha Trang, I headed right over to the supply warehouse, to lay claim to the materials that Phu Cat needed. When I arrived at the warehouse, I was surprised to see a long line of both air force and army personnel sent as scavengers from military posts all over South Vietnam. That’s when I realized this wasn’t going to be as easy as I had thought.

The airmen assigned to the warehouse had been worked to a frazzle, they were spread thin ….and in foul humor. Realizing I would not be able to submit my material request until at least the next day, I went

through the warehouse, looking for the materials needed at Phu Cat. I hoped to find and mark them so they could be readily identified and shipped off asap. Surprised again, I found none of the supplies and equipment on my list. I got in line once more, and when it was my turn to submit my requirements, I was told to just leave my report and come back the next day. With nothing else to do, I found my quarters, and then took a nice swim in the South China Sea. It was wonderful. I also found a Red Cross center, occupied by two American donut dollies. Not having seen any Western women for quite some time, I hung around their compound like a love struck school boy.

The next several days were spent trying to wrangle the needed materials from members of the other U.S. military facilities who had shown up looking for goods. Most were disappointed at what was available at Nha Trang and full-scale bartering and trading activities ensued. As it turned out, few if any had anything, we were in need of at Phu Cat, and many were short of the same items we were. The best I could do was leave my list of requirements with the ill-humored on-site staff, who said they would look at it at some time in the future and ship whatever they could find. True to their word, they eventually sent a large amount of materials and equipment to Phu Cat, unfortunately it was surplus junk they didn’t want to deal with at Nha Trang, not what we needed or requested. So, the whole detail turned into a bungled mess…. what we in the military called a clusterf..k. (Kind of like the whole damn war) But I did go out on the road, while still at Nha Trang, on one detail searching for material. A vehicle convoy, which lasted two days. That was unsuccessful as well, but interesting.

Shanghaied

Packed up and ready to head back to Phu Cat after the 2nd week, I was stopped on the flight line by an Air Force officer. “Campo is it?” He asked, trying to read my nametag. “Campolo, sir”, I replied. He looked me over and ordered me to head back into the small Nha Trang air terminal.

Damn, what the hell did I do now? I wondered.

As it turned out, the officer, a major, had no issue with anything I had done, he just needed another body to load cargo aircraft for the next couple of weeks. (A beefy guy, wide in the back with a distinctive brow ridge, apparently) He explained that I would load and unload any and

everything at each base or airfield on designated flight routes. He officially dubbed me an “assistant loadmaster”. (In other words, a pack mule) When I put up concerns, he assured me he would contact my superiors at Phu Cat and let them know I would be unavailable for a short time. He sweetened the pot by guaranteeing me flight pay for three months-time. That along with my regular pay and the hazardous duty pay I was already receiving for being in Nam, translated into a nice round figure. Now he had my interest. Most of the money we made over there was put into bank accounts for us, as there wasn’t any place to spend much of it anyway. I was building up a nice fat nest egg. And apparently I wasn’t as invaluable as I thought, because no one from Phu Cat put up a fuss over my abduction by the Major.

So, the next three weeks found me flying around the Central Highlands of South Vietnam, loading and unloading aircraft. It was almost one month before the major released me and I was able to return to Phu Cat.

See the War in Nam in your Cargo plane

The first aircraft I was assigned to on these missions was the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, an aircraft I was already familiar with, having traveled on one over much of the Central Highlands of South Vietnam at one time or another. But loading and unloading the aircraft brought me a new appreciation for this beast of burden. We’d load pallets of goods on the ground, then roll them up the reclining back gate and strap them in. Unloading was much quicker, of course, especially those instances when we dropped pallets of goods while still in the air. When this occurred, it was done at low altitude and speed, because the landing strip was too short, compromised or under attack. We also transported troops, Vietnamese civilians and their livestock on occasion. Whenever we transported livestock, the interior would require a good hosing down, as pigs, sheep and chickens did not enjoy flying. (Nor did some of those tending them)

I mostly lived on these aircraft for three- and one-half weeks, and the least favorite aircraft of which I was assigned to was the Fairchild C-119. The “flying boxcar”, as it was called, dated back to pre-Korean War days, and was loaded from the rear also. Smaller than the C-130, and less durable, the aircraft held no charm for me.

One of the missions I went out on was on a C-123 Provider. Also built by

Fairchild, the C-123, infamous for dispersing the lethal toxin Agent Orange throughout the war, was the smallest aircraft I flew on. Flying out of Pleiku, the mission was a resupply effort for the Marine outpost at Dak To. The outpost had been under attack on and off and though our landing was uncertain, we made it in, rubber side down, and got out of there in a damn hurry! Not a fun trip.

Several of my flying days were spent on a Douglass C-47 Skytrain. This was my favorite aircraft by far. Notable as the WWII paratrooper carrier, it was another durable vessel capable of flying under many adverse conditions. Most of the duty on this aircraft involved moving people; troops, civilians or both. We always left the jump door open, and took turns sitting on the floor, hanging onto the webbing with our legs dangling out. From the air, Vietnam was a beautiful country and those flights on the C-47’s, legs dangling in the wind, lost in my thoughts, was to be the most pleasant of all my time in Vietnam.

The flight crews on all of these aircraft had my admiration. Up and down, day and night through all kinds of weather and conditions. And although the Vietcong had no air force, and the North Vietnamese knew better than to send it’s Russian Migs up against the formidable American flying machines, the VC still managed to cause problems. They would sit off the end of the runways and shoot at the planes landing and taking off, usually with recoilless rifles or AK-47’s. To counter that threat, the ascents and descents from all of these airfields and bases were very steep.

The pilot and co-pilots carried their own “butt plates” with them. These were steel plates, formed in the shape of the human seat, which placed over the aircraft seat offered the crews protection from ground fire. It was a bit humorous, watching senior officers carrying this comical looking device around with them, but it no doubt saved a lot of lives and injuries. Weather was also a considerable factor in the Southeast Asian theater. Fog, heavy cloud cover and monsoon rains made for some treacherous flying, and many aircraft in the conflict were lost as a result of it. The Central Highlands of South Vietnam was loaded with mountain ranges, so that hazard was added to the mix. I cannot say enough about the courage and dedication of all of the flight crews who dealt with these conditions on a day to day basis.

A flight to remember

My last flight assignment during this time, was on another C-130, and it was a memorable one. The loadmaster and I had worked together for a couple of days on the same aircraft. Loaded up and headed down the runway, we took our usual seats in the far back, opposite of each other. There was an old parachute on one of the seats, that we hardly took notice of, up until that point. Flying out of Pleiku airbase, we left around mid-afternoon. As usual, the ascent was steep, but not as steep as needed, evidently, because we were soon hit by ground fire from a Vietcong recoilless rifle. The round hit the C-130 in the tail section, and for a moment the aircraft shuddered like a dog in the rain.

A bit stunned, the loadmaster and I looked at each other, then at a small hole below the tail section which was clearly visible. The wind now whistled through the hole, canceling out the usual noise and racket the large aircraft made. As if on que, we both looked at the lone parachute sitting on the webbed seat, and then at each other with a blank stare. (Who would get it?)

Almost immediately one of the pilots came down from the cockpit, walked back and inspected the damage hole. He made a couple of comments about it not really being a “big deal”, made a hand gesture indicating he was not impressed, and walked back to the front of the aircraft. We watched him a bit anxiously as he climbed back up to the cockpit.

Soon, we felt the aircraft turning around and descending in altitude. In just a short time, we landed back at Pleiku, where a couple of emergency vehicles waited on the runway. They were not necessary, however, as the minor damage to the tail did not affect the operational capability of the stalwart C-130 in the least.

Our nerves, however, were definitely affected and we exited the aircraft on wobbly legs. The damage to the tail section was visibly evident, but not really that bad considering the hit it had taken. The loadmaster and I were given a couple of days off, and the major back at Nha Trang, upon hearing of the incident, allowed me to return to Phu Cat to resume my normal duties. The Air Force did me a good turn by continuing my flight pay for several more months, well into my next duty station at March Air Force base in Riverside, California even though I no longer flew on any missions. In my second month of duty at March Air Force base I was given the opportunity to fly to Hawaii and stay for a week, if I agreed to act in my old capacity as an “assistant loadmaster”. (Mule again!) Not wanting to pass up a free trip to Hawaii, I agreed to go. The aircraft turned out to be another C-119 flying boxcar, which I disliked, but had a great time in Hawaii. On the return trip, the last item I off loaded from the C-119 was a surfboard I had paid twenty dollars for in Honolulu. (I always was a scrounger)

Those were the last of my flying days with the U.S. Air Force. Manure clean-up, shootings and sick passengers aside, I thoroughly enjoyed the duty. And Phu Cat airbase was turned over to the South Vietnamese just one year after I left.

Those were the last of my flying days with the U.S. Air Force. Manure clean-up, shootings and sick passengers aside, I thoroughly enjoyed the duty. And Phu Cat airbase was turned over to the South Vietnamese just one year after I left.

In 1975, it fell to the North Vietnamese Army.

Click on any photo to enlarge

Copyright protected, all rights reserved © Joe Campolo Jr, You are welcome to share Joe’s blogs in their entirety, crediting him as the creator

Great story Joe.I was at Pleiku 1966.

Glad you like the story Pete. You were there quite early in the mix. Glad you made it back. Welcome home!

P.S.Got your book the Kansas NCO from my daughter for xmas it is a good story for sure thanks for signing it.

Your welcome, Pete, glad you enjoyed it. “Back To The World” is the sequel to “The Kansas NCO”, and “Three Wars”, my last book, is a prequel that completes the trilogy.

I flew in a few C130’s C47’s and the A1E skyraider from Bien Hoa to Udorn Thailand then we flew A1’s back to bien Hoa for repairs then hopped anything heading back to Udorn which was my TDY.Then flew Goony Bird back to Pleiku for the rest of my tour. Then when we rotated out had to fly C130 to Danang then back to the world via Commercial airline.

Never flew in the A1’s, I’m sure that was an experience, Pete.

Joe, I love your story & the posted photos down memory lane that appeared in the Kenosha Evening News. As an Army grunt I was afforded the opportunity to have flown in some of these aircraft and of course as a paratrooper I am quite familiar with the 130. I am particularly struck by the photo of Nha Trang as it is no way, shape of form anything like I remember it to be way back in 1966 en route to Taiwan for an R&R. Now, having said that I do remember the beautiful beaches of that place, even back then. I also have a fond memory of the Pleiku airbase as that was where I made my escape from Nam back to the world on a 141. Again, I thoroughly enjoyed your story and posted photos. Thanks for posting.

Glad you enjoyed the story Duke….and glad we both made it back. Some of those old birds are still sailing the airways today. Thanks for the feedback, very much enjoy hearing your experiences as well!

Joe, great story and sense of humor. Thank you, too, for the education and for keeping our legacy of Vietnam Veterans alive.

Thanks John, I enjoy your stories as well!