Introduction

Tom in Vietnam

Tom Keating, a writer, served in the United States Army, Long Binh in the Republic of Vietnam, from 1969 to 1970. He served with the 47th Military History Detachment, attached to the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Logistical Command, and Headquarters Company, US Army Vietnam, (USARV) also in Long Binh. Twice awarded the Army Commendation Medal for his service in-country.

Honorably discharged, Tom attended Boston University and completed his Master’s degree in Education, and taught in the high school in Burlington, MA for eight years. A career in corporate media communications followed, including Internet learning design.

He is currently writing a memoir of his military experiences in the US Army, 1968 to 1970 entitled “Yesterday Soldier”. His story “Convoy for the Con Voi” was published in “War Stories 2017”, an anthology edited by Sean Davis.

Tom has attended the writing program for veterans at Boston College under the direction of Roxana Von Kraus since 2017, and was twice accepted at the Joiner Institute’s Master Class at the Joiner Institute Writers’ Workshop Festival at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

He and his wife live in Needham, MA and he is an active member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Post 2498, Needham and is committed to assisting veterans of all ages.

Please enjoy Tom’s story.

A Convoy for the Con-Voi (Elephant)

122 rocket launcher, a VC favorite used to pound U.S. military facilities

In 1969, I was re-assigned to a headquarters unit of a large logistics support base, at Long Binh Post, northeast of Saigon. Enemy rockets shelled us regularly, and they were constantly trying to attack us with commando (sapper) raids. One got used to the alert sirens, crouching in sand-bagged bunkers, waiting for the mortar or 122-millimeter rocket attacks to end, hearing the all clear sirens, then climbing out of the bunker to return to work, which in my case, was typing construction contracts for US firms to build more military bases in country. I was one of the many “support troops.” Rear Echelon Mother Fuckers, the grunts called us. We lived on large bases, relatively safe and in comfort. Hot food, plenty of water, only pulling bunker guard duty or small sweeps outside the wire. I wasn’t on the job long when my commanding officer called in and said,

“Keating, go with Joe and get my elephants.”

“Sir?” I asked puzzled. He looked at me for a second, then he remembered I was the new guy. He explained.

The South Vietnamese army, as well as the VC depended on elephants for transport

The colonel was leaving Vietnam soon and had ordered some decorative, ceramic elephants from a local factory to bring home to Georgia. These elephants were made of china or clay, fired and glazed and brightly colored. They were hollow like a chocolate Easter bunny. They stood about one meter high and people used them as plant stands in their homes. GIs called them BUFEs, Big Ugly Fucking Elephants, and my Colonel wanted me to drive to the factory somewhere in the countryside, pick up the elephants and bring them back to his quarters before he went home.

The local factory was about fifteen kilometers (klicks) from our base. It was in the middle of nowhere, and near a US Army combat base. Shit, that was not good. I knew that combat bases were always located where the enemy was most active in an area.

Joe, an E-5 SGT who had been there on other trips, was gonna be the driver. The idea was to show me the way to the factory so I could do the next trip for the officers. While he signed out the jeep, I put four canteens of water in the back and signed out our weapons. We joined a small MP truck convoy that was going to the combat base near the factory.

They called it the Highway of Death for good reason

The convoy commander, a young lieutenant (we called them ELL-TEEs) called all the drivers together to go over the basic rules of the convoy. “Keep your interval between vehicles. Don’t let any fucking gook vehicles in the convoy, or ARVNs (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), either. Never stop, no matter what. If fired on, speed up and get the fuck out of the kill zone. Got it?”

Everyone nodded. Convoys were always enemy targets. The truck drivers and their relief drivers carried M-16 automatic rifles. They sat on their armor-plated flak vests as extra protection against what are nowadays call IEDs, but back then we called them command detonated mines. They strapped on their steel pots. Joe and I did the same.

Our convoy went out the main gate of the base, the LT in the lead in his jeep with its M-60 machine gun on the mount. Another jeep brought up the rear, also with a machine gunner.

I thought, “Nobody back home would believe that I was in an armed convoy going to an enemy-held area to get fucking ceramic elephants for an officer’s mid-century ranch-style house in Georgia. Great.”

As we turned onto Highway 1, Joe pointed out an elderly, bearded Vietnamese man wearing a NON-LA, the famous Asian conical hat made of reeds, sitting by the side of the road.

“See that Papa-san?” he said. “He’s counting the vehicles in this convoy. He’ll report to the VC how many vehicles we have, and where we’re heading, north or south. There’s a gook at every exit on the post.”

I looked over at the old man – he was using his Buddhist beads to count our trucks.

The convoy moved slowly. The tropical sun beat on us, but the slight breeze as we drove gave us some relief. We had travelled about one kilometer into the trip, when I heard a sharp screeching sound up ahead, then a blaring truck horn, followed by a loud crunch. The convoy speeded up. We did the same.

As we zipped ahead, I saw a crushed Vespa motor scooter in the middle of the road.

One of the trucks in the convoy had run over it. It must have slipped between the trucks. I didn’t see the Vespa driver, but there was a lot of blood on the road, and a smear of blood led off to the shoulder where a cluster of Vietnamese was shouting at the convoy.

“Dung Lai! Dung Lai!” (Stop! Stop!

Nobody stopped.

We drove on.

An hour later, Joe turned off the highway and onto a rut-filled dirt road, red dust spilling behind us. We were in the boonies, some place in the middle of rice paddies and jungle. The elephant “factory” was a low rambling one-story structure made from sheets of corrugated metal. Two ceramic elephants were standing on either side of the entrance. A hand-painted sign in Vietnamese said CON VOI (Elephants) over the entrance.

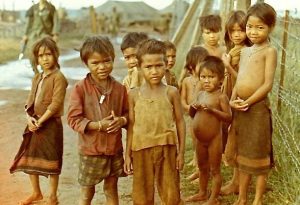

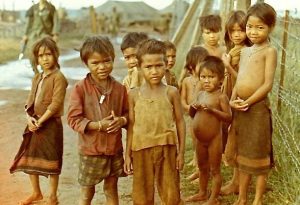

Montagnard children of the Central Highlands of South Vietnam

Joe parked the jeep and entered the factory to check on our elephants while I stood guard at the jeep in the hot sun. I took off my helmet, and put on my boonie hat and was drinking from a canteen when some Vietnamese kids from the little village next to the factory gathered around the jeep. They were all thin, black haired and smiling. They asked for cigarettes with the universal sign language of two fingers at the mouth. I obliged and passed out my Marlboros.

One kid, he looked about seven years old, begged for a cigarette and I gave him one. I laughed when he whipped out a Zippo lighter to light his buddies’ cigarettes.

I showed them a magic trick I learned from watching old Laurel and Hardy movies, where Stan would seem to take off his finger and put it back on. They shrieked and laughed at the trick and wanted me to do it again. They spoke no English, but, using my bad Vietnamese, I did get them to count, “một, hai, ba,” before I put my finger back together a few more times.

Joe returned with the workers and they carefully placed our two brightly colored elephants into the jeep. After covering them with a canvas tarp, I gave the kids the rest of my Marlboros and we drove away.

It was getting late, and we didn’t want to drive back to Long Binh Post alone, at night. Night time belonged to the VC. We checked in at the combat base near the factory for the night. The MP at the gate told us to keep our weapons handy. Intel indicated possible enemy activity.

Anywhere outside the wire was “Indian country”.

We didn’t get much sleep that night, awakened by artillery fire and the sound of flares popping into the darkness, and the brrappp! of mini guns firing red lines of bullets down from gunships onto some poor bastards outside the perimeter.

I guess Intel was right for once. Our elephants were snug and covered in the back of the jeep. When we left the base the next morning, sure enough, I saw an old man sitting outside the gate, watching and counting.

We returned to Long Binh Post and Joe drove to the officers’ quarters where we dropped the elephants off at the Colonel’s air-conditioned trailer. A few days later, he shipped his two elephants home with him and left Vietnam. But before he left, the colonel wrote recommendations for bronze star medals for both of us. For completing “the mission.”

His words were “For Hazardous duty” on the citation. Thankfully, higher headquarters denied the recommendations. It would have been so embarrassing to have to tell people, “And I got this medal here for delivering plant stands.”

I never had to drive back to the factory, the village, and the kids. The factory owner started selling his elephants in a shop on our base not long after that first trip. He was doing great business when I went home three months later – without any elephants.

END

Thomas Keating

The main gate at Phu Cat was a welcome sight for our convoys

Joe’s Note: While stationed in the Central Highlands of Vietnam in 1970, I also went out on many small convoys similar to the one Tom was on. (No elephants,that I remember)

Many were without incident, however we did experience difficulty and hostilities on several of them. Most hostilities were from local Viet Cong along the route, on one occasion a soldier from the local militia known as “White Mice” fired on us. That almost turned into a deadly shoot out. On other occasions, the U.S. army 173rd airborne, in large Deuce and a half trucks, ran us, or attempted to run us off the road. They found sport in chasing our smaller Air Force vehicles, when they could. It was a bit of a game for them, so we didn’t begrudge them too much, but it was not pleasant!

(click on any photo to enlarge)

About the Author

Joe Campolo Jr.

Joe Campolo, Jr. is an award winning author, poet and public speaker. A Vietnam War Veteran, Joe writes and speaks about the war and many other topics. See the "Author Page" of this website for more information on Joe.

Guest writers on Joe's blogs will have a short bio with each article. Select blogs by category and enjoy the many other articles available here.

Joe's popular books are available thru Amazon, this website, and many other on-line book stores.

Good article

Agree George, many people have enjoyed Tom’s story.

Good article Tom. Was in a few of those convoys back then, Yes sir, quite an experience.

Great story, Tom. We grunts were sometimes transported to a new AO via a convoy of trucks.