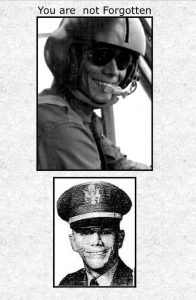

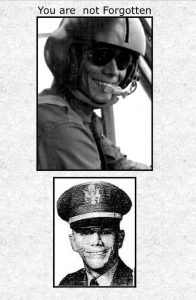

Major Michael O’Donnell

Major Michael O’Donnell was a helicopter pilot killed in action near Dak To, Vietnam in March of 1970. Although I did not know Major O’Donnell we were in Vietnam at the same time, and in some of the same places. This is a poem he penned three months before his death.

Major Michael O’Donnell was a helicopter pilot killed in action near Dak To, Vietnam in March of 1970. Although I did not know Major O’Donnell we were in Vietnam at the same time, and in some of the same places. This is a poem he penned three months before his death.

If you are able,

save them a place

inside of you

and save one backward glance

when you are leaving

for the places they can

no longer go.

Be not ashamed to say

you loved them,

though you may

or may not have always.

Take what they have left

and what they have taught you

with their dying

and keep it with your own.

And in that time

when men decide and feel safe

to call the war insane,

take one moment to embrace

those gentle heroes

you left behind.

~Major Michael Davis O’Donnell

1 January 1970, RIP

Updated: May 24, 2024 at 5:13 am

About the Author

Joe Campolo Jr.

Joe Campolo, Jr. is an award winning author, poet and public speaker. A Vietnam War Veteran, Joe writes and speaks about the war and many other topics. See the "Author Page" of this website for more information on Joe.

Guest writers on Joe's blogs will have a short bio with each article. Select blogs by category and enjoy the many other articles available here.

Joe's popular books are available thru Amazon, this website, and many other on-line book stores.

Major Michael O’Donnell was a helicopter pilot killed in action near Dak To, Vietnam in March of 1970. Although I did not know Major O’Donnell we were in Vietnam at the same time, and in some of the same places. This is a poem he penned three months before his death.

Major Michael O’Donnell was a helicopter pilot killed in action near Dak To, Vietnam in March of 1970. Although I did not know Major O’Donnell we were in Vietnam at the same time, and in some of the same places. This is a poem he penned three months before his death.

Major Michael O’Donnell’s poem is very well known among veterans. He was killed when I was in Vietnam in a battle I was indirectly involved with.

Joe Campolo Jr

I would love if you were able to tell me some of your stories if you would/could. I am writing a book about Vietnam, and I’d like it to include some real perspective from the men who were there. I know several Vets who won’t talk about it, and that’s fine if you can’t.

Thank you for your service sir.

-Ryan

I can talk about most of my experiences in Vietnam, Ryan, though some I will never be able to talk about. I’ll help you if I can, I’ll contact you via email.

12 years after I left Vietnam the PTSD I brought back and refused to acknowledge came crashing into my life. Major O’Donnell’s poem allowed me to look at what happened and to feel sadness and to cry. Thank You, Sir.

Welcome home Brent, glad Major O’Donnell’s poem brought you some relief.

SYNOPSIS: Kontum, South Vietnam was in the heart of “Charlie country” —

hostile enemy territory. The little town is along the Ia Drang River, some

forty miles north of the city of Pleiku. U.S. forces never had much control

over the area. In fact, the area to the north and east of Kontum was

freefire zone where anything and anyone was free game. The Kontum area was

home base to what was known as FOB2 (Forward Observation Base 2), a

classified, long-term operations of the Special Operations Group (SOG) that

involved daily operations into Laos and Cambodia. SOG teams operated out of

Kontum, but staged out of Dak To.

The mission of the 170th Assault Helicopter Company (“Bikinis”) was to

perform the insertion, support, and extraction of these SOG teams deep in

the forest on “the other side of the fence” (a term meaning Laos or

Cambodia, where U.S. forces were not allowed to be based). Normally, the

teams consisted of two “slicks” (UH1 general purpose helicopters), two

Cobras (AH1 assault helicopters) and other fighter aircraft which served as

standby support.

On March 24, 1970, helicopters from the 170th were sent to extract a

MACV-SOG long-range reconnaissance patrol (LRRP) team which was in contact

with the enemy about fourteen miles inside Cambodia in Ratanokiri Province.

The flight leader, RED LEAD, serving as one of two extraction helicopters

was commanded by James E. Lake. Capt. Michael D. O’Donnell was the aircraft

commander of one of the two cover aircraft (serial #68-15262, RED THREE).

His crew consisted of WO John C. Hoskins, pilot; SP4 Rudy M. Beccera, crew

chief; and SP4 Berman Ganoe, gunner.

The MACV-SOG team included 1LT Jerry L. Pool, team leader and team members

SSGT John A. Boronsky and SGT Gary A. Harned as well as five indigenous team

members. The team had been in contact with the enemy all night and had been

running and ambushing, but the hunter team pursuing them was relentless and

they were exhausted and couldn’t continue to run much longer. when Lake and

O’Donnell arrived at the team’s location, there was no landing zone (LZ)

nearby and they were unable to extract them immediately. The two helicopters

waited in a high orbit over the area until the team could move to a more

suitable extraction point.

While the helicopters were waiting, they were in radio contact with the

team. After about 45 minutes in orbit, Lake received word from LT Pool that

the NVA hunter team was right behind them. RED LEAD and RED THREE made a

quick trip to Dak To for refueling. RED THREE was left on station in case of

an emergency.

When Lake returned to the site, Pool came over the radio and said that if

the team wasn’t extracted then, it would be too late. Capt. O’Donnell

evaluated the situation and decided to pick them up. He landed on the LZ and

was on the ground for about 4 minutes, and then transmitted that he had the

entire team of eight on board. The aircraft was beginning its ascent when it

was hit by enemy fire, and an explosion in the aircraft was seen. The

helicopter continued in flight for about 300 meters, then another explosion

occurred, causing the aircraft to crash in the jungle. According to Lake,

bodies were blown out the doors and fell into the jungle. [NOTE: According

to the U.S. Army account of the incident, no one was observed to have been

thrown from the aircraft during either explosion.]

The other helicopter crewmen were stunned. One of the Cobras, Panther 13,

radioed “I don’t think a piece bigger than my head hit the ground.” The

second explosion was followed by a yellow flash and a cloud of black smoke

billowing from the jungle. Panther 13 made a second high-speed pass over the

site and came under fire, but made it away unscathed.

Lake decided to go down and see if there was a way to get to the crash site.

As he neared the ground, he was met with intense ground fire from the entire

area. He could not see the crash site since it was under heavy tree cover.

There was no place to land, and the ground fire was withering. He elected to

return the extract team to Dak To before more aircraft was lost. Lake has

carried the burden of guilt with him for all these years, and has never

forgiven himself for leaving his good friend O’Donnell and his crew behind.

The Army account concludes stating that O’Donnell’s aircraft began to burn

immediately upon impact. Aerial search and rescue efforts began immediately;

however, no signs of life could be seen around the crash site. Because of

the enemy situation, attempts to insert search teams into the area were

futile. SAR efforts were discontinued on April 18. Search and rescue teams

who surveyed the site reported that they did not hold much hope for survival

for the men aboard, but lacking proof that they were dead, the Army declared

all 7 missing in action.

For every patrol like that of the MACV-SOG LRRP team that was detected and

stopped, dozens of other commando teams safely slipped past NVA lines to

strike a wide range of targets and collect vital information. The number of

MACV-SOG missions conducted with Special Forces reconnaissance teams into

Laos and Cambodia was 452 in 1969. It was the most sustained American

campaign of raiding, sabotage and intelligence gathering waged on foreign

soil in U.S. military history. MACV-SOG’s teams earned a global reputation

as one of the most combat effective deep penetration forces ever raised.

By 1990 over 10,000 reports have been received by the U.S. Government

concerning men missing in Southeast Asia. The government of Cambodia has

stated that it would like to return a number of American remains to the U.S.

(in fact, the number of remains mentioned is more than are officially listed

missing in that country), but the U.S., having no diplomatic relations with

Cambodia, refuses to respond officially to that offer.

Most authorities believe there are hundreds of Americans still alive in

Southeast Asia today, waiting for their country to come for them. Whether

the LRRP team and helicopter crew is among them doesn’t seem likely, but if

there is even one American alive, he deserves our ultimate efforts to bring

him home.

Michael O’Donnell was recommended for the Congressional Medal of Honor for

his actions on March 24, 1970. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying

Cross, the Air Medal, the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart as well as

promoted to the rank of Major following his loss incident. O’Donnell was

highly regarded by his friends in the “Bikinis.” They knew him as a talented

singer, guitar player and poet. One of his poems has been widely

distributed.

Thank you for this detailed information Sam.

Cpt.Jerry Pool from my home town

Thank you for the feedback.

Thank you for your service, I to was in combat over in Iraq. I served in the 101st arbn div. I studied a lot of what went on in Ww11 and Vietnam. I appreciate our service people more than words can explain.

Back at you Jay, and welcome home.

I served with the 3/506th, “The Stand Alone Battalion”, 101st Airborne Division. The only battalion of the entire division to participate in Nixon’s Offensive into Cambodia May 5, 1970. Leslie H. Sabo, MOH recipient , KIA, May 10, 1970 along with seven other young heroes lost that day in six hours firefight NVA soldiers.

I first read a Michael O’Donnell poem in 1972 when it was published in a Milwaukee Journal Sunday Edition. It was published as part of an interview the paper had with CPT O’Donnell’s mother who was residing in Shorewood, Wisconsin.

The poem, “Dying in the Sun at Dak To”, reminded me of my experience as a door gunner in Vietnam. Still when I read that poem I am reminded of pulling pitch in the cool pre-sunrise morning, and seeing the sunrise over the South China Sea, then later in the day awaiting a mission while laying on the floor of the aircraft baking in the hot sun. This took place in 1971 during my second tour in Vietnam. It was a time when optimism for success had waned, and many were waiting to go home.

Michael O’Donnell’s poems are powerful reminders for me. Every time I read them I feel them.

Nice to hear from you Robert, and thanks for sharing your experience.