As Covid-19 menaces our society, the promise of a vaccine provides a measure of hope. And with that vaccine comes more controversy. Some people are questioning whether the vaccine will be effective, some are questioning who should get vaccinated first, and yet others are questioning whether they should get vaccinated at all.

Here in the U.S., as in the case of many modern nations, the threat of contagion does not appear often. Most of us are vaccinated against the majority of threats at an early age, so we may not feel particularly threatened by any new virus that pops up. SARS in 2002 and MERS in 2012 were the last major contagions we faced, and they were not nearly so large in scope, nor so devastating as the current Covid virus. The last major threat prior to these was polio. (Aids is not a contagion as such, as it is only spread through specific types of human contact)

The Salk vaccine eventually stopped the polio virus in its tracks, and protected future generations against the deadly malady. But this was many years ago, so we may be somewhat indifferent regarding the necessity to vaccinate against any new bugs that come along.

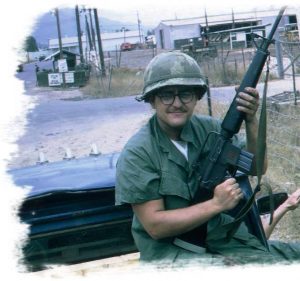

My experience with deadly disease is a result of my service in Vietnam during the war.

The long war in Vietnam was devastating to the Vietnamese people in many ways. In addition to hostile action; poverty, herbicide disbursement and disease took a heavy toll on the nation. The disarray of war along with the tropical climate enhanced the spread of disease. Cholera, other diarrheal diseases and malaria were epidemic. Bubonic plague, leprosy and many types of skin disease also took their toll.

American GI’s were fortunate in that they were inoculated with vaccines to prevent many of the diseases one could acquire during their tour of duty. (Even with the vaccines and remedies, disease accounted for 70% of all medical facility admissions by GI’s during the war)

As the war moved along, American medical services were rendered to the South Vietnamese military and civilians alike. Receiving these services was a great benefit for the Vietnamese people, as they were succumbing to disease almost as rapidly as they were to hostile actions.

However, not all of the maladies ravaging through the war-torn nation had a vaccine. Malaria, some diarrheal diseases, and various fungal afflictions, to name a few, had no preventive inoculation available.

To prevent malaria, which was rampant everywhere in the country thanks to its tropical climate and hordes of blood thirsty mosquitos, chloroquin-premaquin prophylaxis tablets (malaria pills) were issued to American GI’s once a week. These large orange pills were not only difficult to swallow, but created stomach distress and diarrhea in many of those who took them. As a result many GI’s avoided them.

On two occasions during my tour of duty, I accompanied our base chaplains to a nearby leper colony where they brought supplies and rendered aid. I carried supplies to and from the vehicles and huts, but out of fear of the deadly disease, I and others who accompanied the chaplains, avoided contact with the afflicted ones. The chaplains noted that despite their dreaded affliction, all members of the colony took their malaria pills religiously.

Early on, I was one of those GI’s who avoided taking those malaria pills, however after witnessing a member of our unit suffer from the disease, I never missed another dose.

I, for one, am hoping for a quick rollout of the Covid vaccine.

*You are welcome to share Joe’s article, but he must be accredited as the author

You are welcome to share Joe’s blogs on Facebook or any other media, in their entirety with citation acknowledging Joe as the author. Copyright protected, all rights reserved © Joe Campolo Jr.

at my unit, Joe, we took two pills for anti-malaria

Dang, one was bad enough!

Pink pills for weekly and white pills daily, daily. Nice piece, Joe!

Thanks John. If memory serves me, the daily white pills were salt pills.